While significant innovations in FinTech such as AI, big data analytics and blockchain have surfaced rapidly, this global evolution has not been consistent with scholars frequently referencing the cluster-like nature of progression. Through consideration of trends in various countries, this post aims to explore possible explanations for the fragmentation with a specific focus on China.

Inclusivity

China’s strong response to FinTech has been widely discussed with PwC finding that 82% of financial institutions in Hong Kong are aiming to enter partnerships with FinTech start-ups in the next 3 years.[1] Furthermore, ‘BigTech mobile payments make up 16% of GDP in China, but less than 1% in the United States, India and Brazil’.[2] The most prominent argument for this noteworthy involvement is the potential for FinTech to serve the National Congress of the Communist Party of China’s goal of the financial industry serving the real economy. Through innovation, operational efficiency, low costs, and greater accessibility to financial information and data analysis, FinTech forecasts the development of inclusive finance. In this regard, FinTech has been adopted largely due to its perception as a poverty alleviation model, contributing to equality, improving infrastructure and providing less developed regions with affordable and convenient financial services.[3]

Culture & Demographics

A variety of cultural and demographic factors can be identified as pivotal with younger populations being closely correlated with openness to FinTech. Frost cites the connection between cash and older populations versus FinTech with younger populations such as India, South Africa and Columbia.[4]

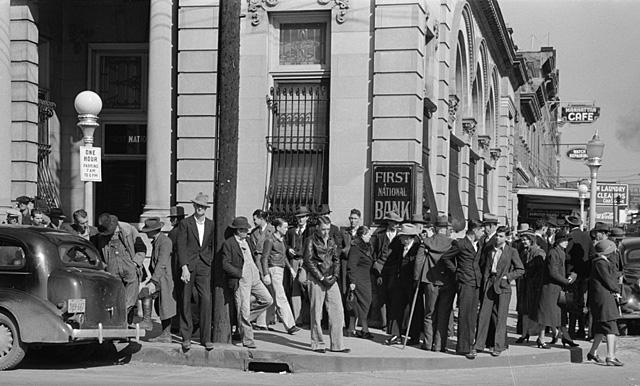

Patterns in China support Jon Frost’s belief in the tendency for FinTech to grow wherever the current financial system fails to meet demand as prior to rapid innovation, China certainly had insufficient ATM and POS facilities for the rural population. Another case of unmet demand proving to be a driving force in the adoption of FinTech can be observed in Kenya where telecom provider Safaricom introduced the mobile money transfer system M-Pesa which has since expanded operations to East Africa, North Africa and South Asia.[5]

Regulation

Another highly influential factor in the potential for countries to embrace FinTech is the nature of regulation. Arguably, for FinTech to be successful, a favourable regulatory environment and responsive audience prove to be non-negotiable. This is especially prevalent when considering rural populations or emerging markets where insufficient financial knowledge run the risk of FinTech being dismissed as complex or acting as a catalyst for a variety of threats. Miao has suggested that the Chinese government should combat these risks by instructing local governments to make financial knowledge an essential aspect of official education while incorporating it into radio, TV and internet sources. She also calls for the necessity of regulatory forces supervising financial institutions ‘to regulate fees… improve the transparency of charging information’ and explore the advantages of big data credit in the market-based pricing of interest rates.[6] The interaction between culture and regulation also plays a fundamental role which is illustrated through the creation of Islamic FinTech. This religion-specific branch aims to be transparent, beneficial for both parties and compliant with Sharia laws.[7]

Conclusions

Evidently a wide range of factors influence worldwide levels of openness to FinTech with inclusivity priorities, culture, demographics and regulation being merely a few. Nevertheless, the fragmented and clustered trends characterizing FinTech adoption today may be set for change due to a noticeable shift towards international collaboration. The Global Financial Innovation Network facilitates cooperation between financial service regulators globally and permits products testing across markets. The Hong Kong Monetary Authority entered cooperation agreements with the UK, Singapore, the Dubai International Financial Centre, Switzerland, Poland, Abu Dhabi, Brazil and Thailand last year illustrating the possibility of a collaborative shift towards the adoption of FinTech.[8]

[1] Yvonne Tsui, ‘FinTech Development in Hong Kong’, ADBI Working Paper Series (2019) p.1.

[2] Yvonne Tsui, ‘FinTech Development in Hong Kong’, ADBI Working Paper Series (2019) p.5.

[3] Zhang Miao, ‘Research on Financial Technology and Inclusive Financial Development’, Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research (2019) p.67.

[4] Jon Frost, ‘The Economic Forces Driving FinTech Adoption Across Countries’, De Nederlandsche Bank Eurosysteem (2020) p.13.

[5] Jon Frost, ‘The Economic Forces Driving FinTech Adoption Across Countries’, De Nederlandsche Bank Eurosysteem (2020) p.10.

[6] Zhang Miao, ‘Research on Financial Technology and Inclusive Financial Development’, Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research (2019) p.67.

[7] Anwar Mokhamad, ‘Islamic Financial Technology: Its Challenges and Prospect’, Achieving and Sustaining Conference: Harnessing the Power of Frontier Technology to Achieve Sustainable Development Goals (2019) p.54.

Yvonne Tsui, ‘FinTech Development in Hong Kong’, ADBI Working Paper Series (2019) p.5.