The Great Depression has been frequently described as ‘one of the greatest disasters in American history’ due to its disastrous impact on income, tax revenue, profits and unemployment.[1] Perhaps unsurprisingly, the adverse impacts on banks in Mississippi were relentless which becomes particularly apparent when considered in conjunction with the impact on national banks. The severity of this impact can be ascribed to the rural, impoverished characteristics of the state alongside the convoluted nature of policy implementation. Mississippi was divided into two Federal Reserve districts with conflicting policies surrounding liquidity provision which has been identified as a contributing factor to bank failures. In 1929 over 80% of people in Mississippi lived in a rural area vs 45% of the general population which illustrates how problematic it can be to generalize the impact of The Great Depression across states.[2]

Understanding the implications of The Great Depression in Mississippi has been an area of interest to scholars due to the uniquely localized business relationships and enduring co-dependency. The bank was undoubtedly a fundamental focal point of the townspeople’s lives with a weekly venture to town being the only alternative to storing cash under a mattress. Credit relationships had a tendency to be local which mitigated the likelihood of moral hazard and adverse selection since long-term relationships decreased the incentive of pursuing short-term gains. However, not all repercussions of localized business relationships were positive as credit rating agencies such as D&B have revealed through their Reference Books (1926-1935) that the highest credit ratings were reserved solely for firms with large net worth’s.[3]

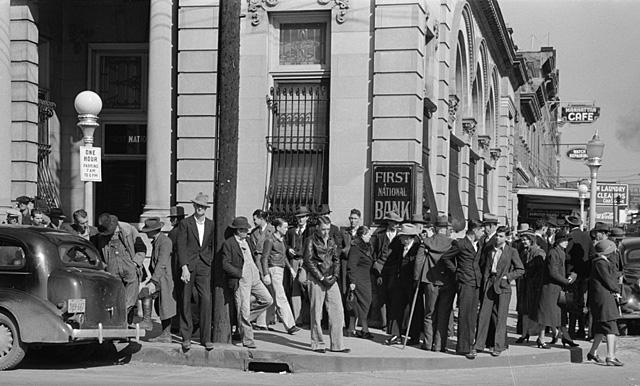

The survival of one small bank; The First National Bank of Oxford, has been regarded as nothing short of a miracle particularly due to its founding only 20 years prior to The Great Depression. Against all odds, FNBO managed to ‘double the balance of its individual depositors’ accounts in the midst of the darkest months of the Great Depression’.[4] Irrefutably, a key factor in the survival of FNBO was the power and influence of small newspapers which contrasts significantly from the easy access to financial information available today. In line with the majority of small towns in Mississippi; there was only one newspaper. The Oxford Eagle was published weekly and displayed quarterly financial statements.[5] The Eagle played an integral role in calming the citizens of Oxford, preventing bank runs and dictating where civilians were willing to put their trust.

Rescuing FNBO…

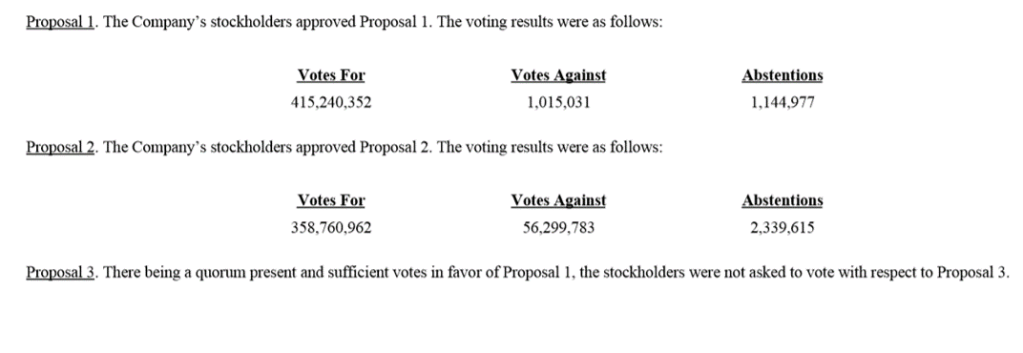

FNBO was forced to close in November 1930 directly resulting from their investments in Guaranty Bank & Trust whose failure outraged the Oxford community. The behaviour of Guaranty’s president, J. A. Smallwood, shocked civilians following the emergence of his $75,000 embezzlement charges illustrating the problematic repercussions of co-dependency between Mississippi banks.[6] In response to the undue closing of FNBO and their favourable media portrayal, the community collaborated to rescue the benevolent bank and preserve its legacy. The development of the ‘Love Plan’ entailed depositors exchanging 25% of their deposits for stock in the bank which would transfer ownership to depositors and provide sufficient cash for meeting immediate needs. Subsequently, in 1931, the Oxford Eagle outlined the plan for the remaining 75% of deposits to be gradually unfrozen: 10% within 30 days from the adoption of the plan, 15% within a year, 25% at the end of year two, and the final 25% at the end of year three. Once the majority of depositors had accepted the plan and met the baseline requirement of holding a minimum of ten dollars in the Bank of Oxford the bank was reopened within five months.

Where is FNBO today?

While the spread of information today may rely on social media and digitization as opposed to newspapers, society still looks to the media in an attempt to attain clarity and transparency surrounding which corporations to trust.

FNBO’s short history indicates that as with the 2007 crisis, survivors of the Great Depression were not dictated by continuity or a rich history. Surviving banks had the capabilities to respond and adapt swiftly to the crisis with community support being the overwhelming advantage for FNBO. Furthermore, the practices of misleading credit ratings and selective credit relationships have been important characteristics of 21st-century financial crises.

The First National Bank of Oxford’s tale of durability offers an important insight into the nature of the Great Depression in Mississippi and its impact on local communities. The story of FNBO remains a watershed in the history of the Great Depression since no other banks in Oxford were able to endure the hostile financial climate. FNB remains open today and proudly maintains its culture of offering a localized service and participates in a variety of community ventures.

[1] Eric Bostwick, “The Little Bank That Could: An Examination of the Historical and Financial Records of One Bank That Survived The Great Depression”, Accounting Historians Journal (Florida, 2019) p.17.

[2] Nicolas Ziebarth, “Identifying the Effects of Bank Failures from a Natural Experiment in Mississippi during the Great Depression”, American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics (2013) p.86.

[3] Mary Hansen, “Credit Relationships and Business Bankruptcy During the Great Depression”, American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics (2017) p.235.

[4] Eric Bostwick, “The Little Bank That Could: An Examination of the Historical and Financial Records of One Bank That Survived The Great Depression”, Accounting Historians Journal (Florida, 2019) p.17.

[5] Eric Bostwick, “The Little Bank That Could: An Examination of the Historical and Financial Records of One Bank That Survived The Great Depression”, Accounting Historians Journal (Florida, 2019) p.27.

[6] Eric Bostwick, “The Little Bank That Could: An Examination of the Historical and Financial Records of One Bank That Survived The Great Depression”, Accounting Historians Journal (Florida, 2019) p.17.